Chris Harrison

Welcome to the website of award-winning author and journalist Chris Harrison.

Welcome to the website of award-winning author and journalist Chris Harrison.

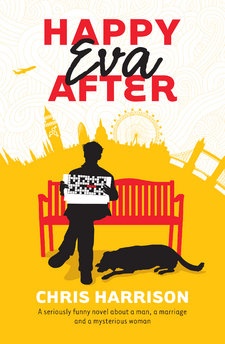

My new book and debut novel has just been released and is available now in bookshops or online. Described by The Sydney Morning Herald as "one of the most delightful books I've read in a long time", HAPPY EVA AFTER is a comedy set in a language school where a teacher and his tongue-tied students unwittingly prove that a little learning is indeed a dangerous thing.

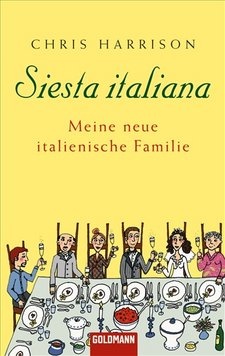

If non-fiction is more your thing and you fancy a trip to southern Italy, then come along for the (bumpy) ride in my bestselling travel memoir HEAD OVER HEEL - a comedy of love and hate on the 'heel of the boot'. Whether you're a hopeless romantic or a hot-blooded bloke, jump in the Fiat and fasten your seat-belt!

If you're prone to carsickness you can hang around here and read my weekly columns, which have appeared across a variety of newspapers and websites.

Click the journalism tab to sample my other writing, which has featured in The Guardian, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age,The Courier Mail, Sports Illustrated, Inside Sport and elsewhere.

Or if brevity floats your boat, you can follow me on Twitter @harrisonwriter

Wherever you choose to wander, I hope you have fun.

Happy travels,

Chris